Shhh!

This may be nothing like the final logo, but it might also be about 90% of it… We’ll see…

Notes from the drawing board

Shhh!

This may be nothing like the final logo, but it might also be about 90% of it… We’ll see…

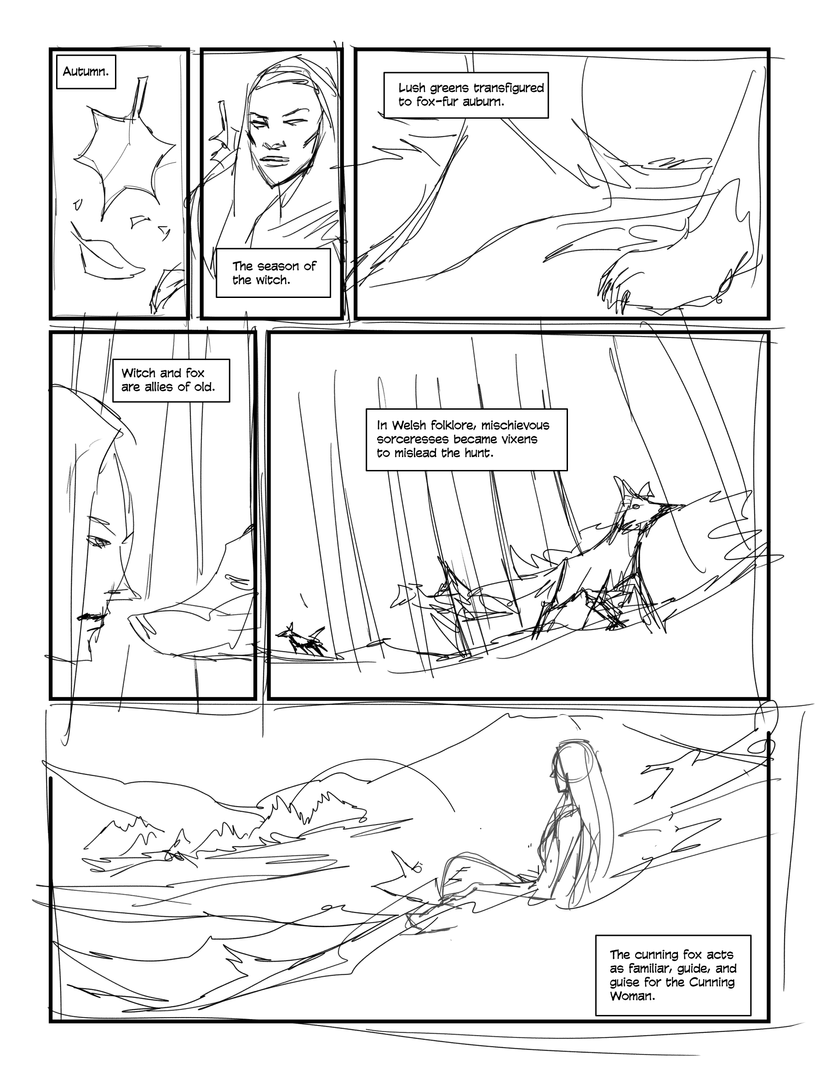

Started pencilling this one, and I kind of liked the texture, and I wanted an old penny dreadful feel to it anyway, and lo, we ended up with a pencilled page…

https://open.spotify.com/track/4cvlph4w9RGpSH8tf1c885?si=AoIFA2-aRQiggGxtTYVJmw

Here’s the pencils for this one

Aooowooo wereloves of legend…

It’s a beetles concert.

Look, I’m tired and I apologise for spelling out the joke. But there it is.

February 1838. 18-year-old Jane Alsop is startled by hammering at her door. A man outside shouts that he’s a police officer and requires a lamp. Jane’s light reveals the caller for what he really is: Spring-Heeled Jack. The Terror of Old London Town.

——

The entity we now call Spring Heeled Jack first made its self known late in the summer of 1837 when a curious shape changing creature – reported variously as an imp, a white bull, a ghost, an armour clad man and a bear – terrorised the satellite villages of the capital. By January 1838, these reports had grown so numerous that the then Lord Mayor of London, Sir John Cowan, convinced that pranksters where to blame, vowed that those responsible would be caught and punished. London was in the grip of a sort of mass hysteria with the thing – now christened Spring Heeled Jack because of the immense leaps it seemed capable of – being sighted all over the city, yet somehow always evading capture.

It was at the height of this panic, on the evening of the 20th of February 1838 that an eighteen year old girl by the name of Jane Alsop was startled by a furious knocking at the door of her family home in the district of Bow. Jane answered the door to an excited gentleman who claimed to be a police officer. He breathlessly informed the young lady that he believed he had successfully apprehended non-other than Spring Heeled Jack himself and implored her to fetch a lamp. When Ms. Alsop returned however, the lamp’s light revealed the caller’s peculiar attire “he was wearing a kind of helmet, and a tight fitting white costume like an oilskin. His face was hideous; his eyes were like balls of fire. His hands had claws of some metallic substance”.

The man attacked Jane, tearing at her clothes with his talon-like hands but vanished into the night when, alerted by her screams of terror, members of her family came to her assistance. In a statement given to the Lambeth police Jane swore that the caller had “vomited blue and white flames” during the assault.

Only five days later another eighteen year old girl, this time named Lucy Scales was walking with her sister on their way home from visiting their brother. As the women travelled along the thoroughfare known as Green Dragon Alley a figure sprang from the shadows and attacked Lucy, apparently breathing fire into her face. The assailant then strolled calmly away as Lucy’s sister tried desperately to tend to her sibling, calling out for help from anyone who might hear. Lucy was rendered insensible by the attack and fell into violent spasms which lasted several hours.

These reports and others like them cemented Jack’s reputation as a kind of fiendish cultural icon for the new Victorian age, a position which he held up until his more vicious namesake Jack the Ripper began his reign of terror. Penny Dreadfuls, the day’s version of pulp fiction magazines, telling of the phantom’s exploits were published and plays bearing his name were staged in many of the city’s fleapit theatres. Soon however, the attacks became less frequent and slowly but surely Spring Heeled Jack faded from real life terror to urban myth. Over the next few decades periodic sightings of the entity came from as far afield as Sheffield, Northampton and Lincolnshire. On one occasion he was even shot by a soldier when he appeared at an army barracks in Aldershot, the bullets apparently having no adverse effect.

Jack still crops up now and again; most recently in South Herefordshire during the late 1980s when a Mr. Marshall was slapped by a strange, jumping figure that bounded away across open fields cackling after the attack. Nearly two centuries since Spring Heeled Jack’s first appearance, it seems we are no closer to solving the mystery of who or what it actually is.

Autumn. The season of the witch. Lush greens transfigured to fox-fur auburn. Witch and fox are allies of old. In Welsh folklore, mischievous sorceresses became vixens to mislead the hunt. The cunning fox acts as familiar, guide, and guise for the Cunning Woman.

—-

September 22nd marks the 2020 Autumnal Equinox in the Northern Hemisphere. Mabon, Harvest Home, the Feast of the Ingathering, Meán Fómhair, An Clabhsúr, or Alban Elfed are names given to Neo-Pagan festivals which take place at the turning of the season. All are thanksgiving festivals – giving thanks to the Gods and Goddesses for Summer’s bounty and hoping to secure their blessings for the months ahead.

The American poet, academic, and Neo-Pagan Aidan A. Kelly is widely credited with introducing the name Mabon in the 1970s. Mabon ap Modron is a prominent figure in Welsh mythology, said to have fought alongside King Arthur. Tales of Mabon ap Modron are said to stem from an older Celtic God, or demi-God figure, Mabon – the son of the Mother Goddess – and so the modern festival is named in his honour.

The word witch has been used in a derogatory fashion for many centuries, only to be embraced and reclaimed by magical practitioners in the last hundred years or so. Before this reclamation, the most simple definition of witch was a practitioner of malevolent Black Magic; using their knowledge and skills to (attempt to) cause hardship, misfortune, and harm to others. Yet, there have always also been those who practice White Magic; using their powers to help and to heal. Rather than “witch”, these Folk Healers have long been known as Wise Women and Men (“dynion hysbys” in the Welsh Language), or Cunning Folk, amongst other names.

The distinction between evil, Satanic witches and the benevolent, often Godly, Cunning Folk was so clearly defined in the minds of the general populace that, even during the Witch-Trials of the 17th-century, few of these Wise Women and Men stood accused in England or Wales. Of those who did, few Cunning Folk were ever convicted of the crime of witchcraft because, even though there was little or no doubt in the minds of those who knew them that these people possessed magical knowledge and performed magical acts regularly, theirs was a wholly separate class of magic.

The distinction between these two classes of magic and two kinds of practitioners remained clear well into 18th-century until the Witchcraft Act of 1736 was passed. Legally, after that Act came into force, magic no longer existed. Anyone claiming to have magical powers, or to offer magical services was, therefore, a fraud; Wise Woman or witch, the crimes and the penalties were the same. From this point on the line between the two magics became increasingly blurred, and the word “witch” did just as well for anyone.

The mischief of witches is well known […] In North Glamorgan witches sometimes took the form of a fox. The animal baffled the hounds, and led huntsmen into dangerous places. Neither mask nor brush would the huntsmen have when the witch led them. – from Folk-lore and folk-stories of Wales, by Marie Trevelyan (1909)

Both witches and Cunning Folk have their familiars – their magical guides, companions, and helpers. In the case of Cunning Folk, they might be said to be faeries (although it is worth mentioning that, in 17th-century Scotland, several witches were convicted and executed for consorting with the Fae), while the witches’ must surely be demons, but in either case, familiars appeared most often in the forms of animals.

In Japanese folklore, the most popular magical familiar by far is the fox, or “Kitsune“. Kitsune are believed to possess inherent magical powers, and one ancient method of gaining magical knowledge – essentially of becoming a witch – was to feed, befriend, and tame one of these creatures. Kitsune can assume human form and, according to the old legends, particularly enjoy becoming young, attractive women. Many Japanese folk tales tell of men unwittingly seduced by foxy women.

“Certain wicked women, reverting to Satan, and seduced by the illusions and phantasms of demons, believe and profess that they ride at night with Diana on certain beasts, with an innumerable multitude of women, passing over immense distances, obeying her commands as their mistress, and evoked by her on certain nights.” [5] – from Malleus Maleficarum (1486), Chapter III, “How they are Transported from Place to Place”.

The Gandreið – “Witches’ Ride” – long depicted as the chaotic broomstick-flight towards the Black Sabbat – is now interpreted by many scholars of witchcraft not as a bodily flight through the air, but as a spiritual one. The practitioner often guided by an animal on their journey, or sometimes taking the form of an animal themselves. “Sent out” from the physical self via meditation, lucid dreaming, or other Shamanic means, the practitioner (who might call themselves a witch) may become a fox. … a hare, a crow, a cat, a moth… They may see through the eyes of another. Gain knowledge and understanding of the world beyond their own everyday experiences. They may learn the Kitsune’s secrets. They may baffle the hounds, and lead the huntsmen into dangerous places.

Denoon Law fort is a grass-covered hillfort in the Sidlaw Hills, in Angus, Scotland. According to James Cargill Guthrie, writing in 1875, “It was the mythical abode of the elfins and fairies, and formerly a fitting haunt for their midnight revelries.”

—–

Denoon Law fort seems to have been a prehistoric construction added to over many hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of years. The County Angus survey by the Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland (1983), described Denooon Law:

This fort crowns the summit of Denoon Law, a steep-sided volcanic plug on the NW side of Denoon Glen, a narrow valley at the N end of the Sidlaw Hills. The fort is roughly D-shaped on plan with the chord of the D formed by a long straight rampart that stands above the precipitous SE flank of the hill. It measures 105m from NE to SW by 55m transversely within a rampart that measures up to 17m in thickness and over 5m in external height but is clearly of more than one phase.

Where the differentiation is clear, the latest phase of rampart measures about 6m in thickness and overlies the remains of a much thicker earlier rampart. Intermittently visible at the SW end of the fort is an outer face to the later rampart, comprising drystone walling that has, in places, been displaced downslope by the weight of core material behind. This outer face comprises no more than four or five courses of thin sandstone slabs and, although what is currently visible will only be the top of the surviving wall-face, a wall constructed of such material cannot have stood to any great height and what we see today is likely to be the remains of some form of comparatively low revetment.

In both the earlier and later ramparts there is very little evidence of stone within the core and it appears that the material (boulder clay) for both has largely been derived from several large quarries within the interior of the fort. At the SW corner of the fort most of the rampart has been removed, leaving only the lower part of the outer talus. The fort, or at least its latest phase, had two entrances, one on the NE and another on the NW, both of which are crossed by the remains of a narrow, later, wall that runs around the entire circuit of the fort and may be associated with at least some of the buildings within the interior.

In his 1875 book, The Vale of Strathmore; its Scenes and Legends, James Cargill Guthrie gave the following account of Denoon Law, and the faerie legend attached to it:

The Hill of Denoon is steep, and of considerable height, one side of the rock being nearly perpendicular, while the other sides are of tolerably easy ascent. A stone wall, eight or nine feet in thickness, is carried obliquely round the Hill, encircling a space of 340 or 350 yards in circumference. Within this semi-circular and extensive rampart, there are scattered vestiges of the foundations of an immense castellated edifice, with traces of several entrances in the external walls. It is to this Castle, therefore, the following short legend refers.

Eight hundred years have rolled away since the erection of the first Castle of Glamis; yet from the darkness, turmoil, and strife of that early time comes, weird-like, a legend’s muffled chime.

The Hill of Denoon was at that remote period accounted sacred or haunted ground. It was the mythical abode of the elfins and fairies, and formerly a fitting haunt for their midnight revelries.

When the silvery moonbeams lovingly slept in dreamy beauty on the green slopes of the enchanted Hill, and the blue bells and the purple heather were wet with the dew of angels’ tears, arrayed in gossamer robes of bespangled gold, with wands of dazzling sheen and lances of magical brightness, would the troops of elfins flauntingly dance to the

music of the zephyrs, until the shrill cry of the chanticleer put an end for the time to their mystical enchantments.

Suddenly, as in blue clouds of vapour, they noiselessly vanished away, no sound remaining to break the oppressive stillness, save that of the fountain rivulet, as it fretfully leapt from crag to crag, as if piteously regretting the mysterious departure of its ethereal visitors.

Having forsworn the presence and companionship of the terrestrial inhabitants of earth, it was a sacred dictum in the code of the fairies that no habitation for human beings should be permitted to be built within the hallowed precincts of the enchanted ground. Unable of themselves to guard against such sacrilegious encroachment, they had recourse to the aid of, and formed a secret compact with the demons, or evil spirits, whose sole avocation consisted in doing mischief, and bringing trouble and misfortune on those under the ban of their displeasure. By this compact these evil spirits became solemnly bound to prevent any human habitation whatever from being erected on the hill, and to blast in the bud any attempts whensoever and by whomsoever made to break this implacable, unalterable decree.

It was about this time the alarm-note was sounded, as the Queen of the Fairies, who, with an eye more observant than the rest of her compeers, observed one evening in the moonlight, certain indications of the commencement of a human habitation. Horror and dismay were instantly pictured on the fair countenances of the masquerading troops of merry

dancers as the awful truth was ominously revealed to them by the recent workmanship of human hands.

A council of war was immediately held, when it was determined to summon at once the guardian spirits to their aid and protection.

” By our sacred compact,” cried the Queen, ” I command the immediate attendance of all the demons and evil spirits of the air, to avenge the insult now offered to the legions of Fairyland, and to punish the sacrilegious usurpers who dare infringe the sanctity of their mystical domains.”

These demons instantly obeyed the haughty summons, and, in the presence of those they had sworn to protect, they in a twinkling demolished the structure, hurling the well-proportioned foundations over the steep rock into the vale beneath!

The builder, doubtless very much surprised and chagrined when he returned to his work in the early dawn of the following morning, was sorely puzzled to account for the entire disappearance of the solid foundations of the great castle he intended to be erected on the Hill. He did not, however, waste much time, or use much philosophic argument,

on the matter, and gave orders to prepare new foundations of even a more durable character.

The demons, to show their invincible power, and for the sake of more effect, allowed the new foundations to rise a degree higher than the former, before they gave out their fiat of destruction. In an instant, however, they were again demolished, and the builder this time gravely assigning some fatal shock of Nature as the cause of the catastrophe

quietly resolved to repair the damage by instantly preparing new and still more solid foundations.

Additional and more highly skilled workmen were engaged, and everything for a time went favourably on, the walls of the castle rising grandly to view in all the solidity and beauty of the favourite architecture of the period.

Biding their time, the demons again ruthlessly swept away as with a whirlwind every vestige of the spacious halls, razing the solid massy foundations so effectually that not one stone was left upon another!

Things were now assuming a rather serious aspect for the poor builder, who, thinking that he had at last hit upon the true cause of these successive disasters, attributed his misfortunes to the influence of evil spirits. A man of courage and a match, as he imagined, for all the evil spirits of Pandemonium, supposing they were let loose at once against him by the Prince of Darkness, he unhesitatingly resolved to keep watch and ward on the following night, and to defy all the hosts of hell to prevent him rebuilding the projected edifice. The night expected came; but, alas, alas!

“His courage failed when on the blast

A demon swift came howling past,

Loud screeching wild and fearfully,

This ominous, dark, prophetic cry

” Build not on this enchanted ground !

‘Tis sacred all these hills around ;

Go build the castle in a bog,

Where it will neither shake nor shog! ”

In 1987 WTCM-FM DJ Steve Cook played a brand new record called “The Legend” on his show. The song told the tale of the Michigan Dogman – a Werewolf, first sighted in the state in 1887. He was inundated with calls from listeners claiming to have seen the beast.

—-

America is a nation with many, many urban legends stretching back generations; tales of strange, inhuman things lurking out there in the wilderness, or by the roadside, beneath the still black waters, or amongst the vine enshrouded trees. Waiting.

According to Cajun folklore, the Rougarou prowls the swamplands around Acadiana and Greater New Orleans. Sharing many attributes with European Werewolf folklore – the Rougarou is a human who takes on a bestial form as a result of a supernatural curse. In some versions of the tale the curse is self-inflicted by a transgression against the church or God, in others, it is inflicted by a witch. The Rougarou’s curse lasts for one hundred and one days after which time it may be passed on, via a bite, to the next victim.

Rougarou is by no means the only American were-wolf legend, however, and while its roots are unmistakably ancient, the tale of the Michigan Dogman may have much more modern origins.

A cool summer morning in early June, is when the legend began, at a nameless logging camp in Wexford County, where the Manistee River ran.

Eleven lumberjacks near the Garland swamp found an animal they thought was a dog.

In a playful mood they chased it around till it ran inside a hollow log.

A logger named Johnson grabbed him a stick and poked around inside.

Then the thing let out an unearthly scream and came out and stood upright.

These are the opening lyrics of “The Legend” a song written and recorded by Steve Cook, a radio DJ at WTCM Radio in Traverse City, Michigan, USA. Cook played the record on his show on April the 1st, 1987, as a prank. “The Legend” told the fictionalised story of a werewolf-like creature sighted in the Michigan area every ten years since 1887. What Cook was not prepared for, however, was his listeners’ response to the song. Dozens of callers to the show claimed to have seen the beast themselves or to have heard tales of others’ encounters.

Linda S. Godfrey is a Wisconsin-based author and investigator who has been looking into the existence of creatures that fit the description of dogmen, which she calls “upright canines,” since 1991. In a 2017 interview with The Huffington Post, Godfrey told reporter David Sands

“It’s fully canine, walks on its hind legs, uses its forelimbs to carry chunks of … roadkill or deer carcasses.” she said. “They have pointed ears on top of their heads. They have big fangs. They have bushy tails. They walk — most tellingly — digitigrade, or on their toe pads, as all canines do, and that’s something that a human in a fursuit really can’t duplicate”.

Despite having been contacted by over five hundred witnesses, DJ Steve Cook remains unconvinced about the existence of the creature he made famous. In 2015 he told skeptoid.com:

“I’m tremendously skeptical, because I’ve sort of seen the way folklore becomes built from the creation of this song to what it’s turned into … but I do believe people who think they saw something really did see something. I also think the Dogman provides them with an avenue to explain what they couldn’t explain for themselves.”

High above Alderley village in Cheshire, England, lies The Edge. A sandstone escarpment inhabited since Mesolithic times. Local legend tells of The Wizard – an ageless sorcerer. There beneath stone and soil, an army sleeps. Waiting. Only The Wizard can wake them.

—–

The Western archetype of the venerable, long-bearded, staff-wielding wizard, wearing a wide-brimmed hat or hood, most likely comes from the Old Norse God Odin in his Wanderer guise.

The word wizard comes from the Middle English “wysard“, meaning “very wise” (interestingly, an “-ard” ending on many old words simply means “hard“, as in “very” or “lots of“, which makes words like buzzard quite funny).

Alderley Edge is a village and civil parish in Cheshire, England, 6 miles (10 km) northwest of the town of Macclesfield, and 12 miles (19 km) south of the city of Manchester. The village lies at the base of a steep and thickly wooded sandstone escarpment known as The Edge. There, carved into the sandstone, is the face of a wizard. Of The Wizard. There a natural spring drips water into a carved stone cyst. The words “Drink of this and take thy fill – for this water falls by the wizard’s will” are engraved above.

In 1805 a letter was published in the Manchester Mail newspaper, telling the tale of The Wizard of Alderley Edge. This story, the letter writer stated, had been told often by Parson Shrigley, the former Clerk and Curate of Alderley, before his death in 1776. The piece attracted enough attention that a tourist pamphlet was soon printed – expanding the original text somewhat – entitled The Cheshire Enchanter. Below is an extract from that pamphlet.

A Farmer from Mobberley, mounted on a milk-white steed, arrived on the Heath, which skirts Alderley Edge. He was journeying to Macclesfield, to dispose of the horse he then rode at the fair. Deeply musing on his errand, and reckoning on the advantages which might arise from the sale of the animal, he stooped to stroke its neck, and adjust the flowing mane, which the rude wind of the morning had deranged.

On lifting up his head, he perceived a figure before him, of more than common height, clad in a sable vest, which enveloped his figure; over his head, he wore a cowl, which bent over his ghastly visage, and screened not hid, the eyes, that sunken and scowling, were now fully bent upon the horseman; in his hand, he held a staff of black wood, this he extended so as to prevent the horse from proceeding until he had addressed the rider. When he essayed to speak his countenance became more spectre-like, and in a hollow yet commanding voice, he said

“Listen, Cestrian! I know thee, whence thou comest, and what is thy errand to yonder fair! That errand shall be fruitless; thy steed is destined to fulfil a nobler fate than that to which thou doomst him. He shall be mine. Vainly thou wilt seek to sell him; yet go and make the trial. Seest thou that Sun, whose beams just gild the beacon tower? When he shall have sunk beneath the western hills, and the pale moon has risen in his stead, be thou in this place! Nay, fear not! no evil shall betide thee if thou obey. Fare thee well! till night shall close again upon the world. ”

Having said this, he walked away. The Farmer, glad to be re-

leased from his presence, spurred his horse and hastened to Macclesfield.

Here nothing awaited him but vexation and disappointment.

He boasted of the swiftness of his steed—the High blood of his progenitors—his sweetness Of temper and docility—-the surety of his footstep, and pleasantness of pace; he ranked him above all other animals around him, but in vain—no purchaser appeared willing to give the price required, he reduced it to the half, “but still the horse remained unsold.” He thought on the stranger and his morning salutation. He saw the western sky reflect back the last golden ray of the setting sun.

He viewed the Moon rising above the horizon, and mounting “ his milk-white steed,” resolved, at all events to obey the command of the unknown.

He hastened to the appointed spot, afraid to trust his mind to dwell on the idea of the meeting. He reached the seven firs and

condemned his eagerness when he saw the same figure reclining on a rock beneath. He checked his rapid pace and began seriously to reflect on the probability of mischance. Who the being was that had thus commanded his presence! — who had thus foretold the events of the day, he knew not! If he were mortal, he strength and figure held a fearful superiority over him, should his intention be to ensnare him, or to take his life. Yet mortal strength he feared not—he was brave and had learned the science of self-defence at the wakes and fairs, where broils were very frequent. He blamed his hesitation, and accused himself of cowardice, muttering the local phrase. “I defy him !” “ I defy him!” and again set forward at his former pace. Presently he arrived on the verge of the heath and then suddenly stopped. The idea of the Stranger being an evil spirit, seized upon his mind, and subdued his courage. He gazed in trembling anxiety on him as he sat on the projection before him. The calm and apparently sleeping posture of the object abated his terror: yet he took the precaution to repeat all he could remember of a potent charm, taught him by his grandmother, to protect him from the influence of such as he feared the Stranger to be (It might have been “St. Oran’s Rhyme,” or “St. Fillan’s prayer.” But the Legend does not mention by name therefore I will not pretend to say what it was.) He however, began to think of returning, could he do it unperceived; but at that moment the Stranger rose and advanced towards him.

“Tis well,” he said, that thou art come. Follow me, and I will give thee the full price for thine animal.” He then turned down the northern road, the horseman following in silent apprehension. They cross the dreary heath, and enter the Wood—they soon reach the Golden Stone—-then by Stormy Point and Saddle Bole they pass—arrived at this extremity, the horseman seemed ready to exclaim “Speak, I will go no farther.”

At that instant, from beneath their feet issued distinctly the neigh of a horse. The Stranger paused, again the neigh of a horse was heard—he reared his ebon wand, and hollow sounds, like the murmuring of a distant multitude, mingled with the horse’s neigh, which was again repeated. The Farmer gazed in wild affright, on his guide, and now first perceived that he was a Magician; to his terrified imagination, he, at that moment, appeared to have increased in stature far beyond the height of mortal man—his mantle, which now flowed loosely from his shoulders, added to the commanding air of his figure, and, with his arm and wand extended, he muttered a spell—the earth was immediately in a convulsive tremor, and before the Farmer could recover his breath, which had been suspended in his fright, the ground separated and discovered a ponderous pair of Iron Gates.

The Magician again waved his wand, and with a noise, as it were of an earthquake, the gates unfold. The animal, terrified at the violent concussion, reared and plunged, and threw his rider to the ground. Soon as he recovered his bewildered thoughts, he kneeled before the Enchanter, and in piteous accents, besought him to have mercy on him, and to remember his promise, that “no evil should betide him if he obeyed.” “Nor shall there,” answered the Enchanter, “enter with me, and I will shew thee what mortal eye hath never yet beheld.”

The Farmer obeyed, and beheld a vast cavern, extending farther than his eye could reach; enlightened only by what appeared to be phosphoric vapours, its high arches were adorned by the distillations from the earth above, which had petrified into innumerable points, and illuminated by the unsteady light of the vapour, seemed, at one moment, to increase in number and beauty, and the next to vanish or recede from the view.—–Ranged on each side were horses, each the colour and figure of his own, tied to stalls formed in the rock. —-Near these lay soldiers, accoutred in the heavy chain mail of the ancient warriors of England—these seemed to increase in number as he advanced. In chasms of the rock he saw large quantities of ore, and piled in vast heaps, coins of various sizes and denominations. In a recess, more enveloped in gloom than the rest, stood a chest; this the Enchanter opened, and took from it the price of the horse, which the Farmer received, and fear being lost in astonishment, he exclaimed, “What can this mean?” “Why are these here?” The Enchanter replied,

“These are the Caverned Warriors, who are doomed by the good Genius of Britain, to remain thus entombed until that eventful day, when over-run by armies, and distracted by intestine broils, England shall be lost and won three times between sun-rise and eventide. Then we, awakening from our rest, shall rise to turn the fate of Britain, and pour, with resistless fury, on the vales of Cheshire. This shall be when George, the son of George, shall reign—when the forests of Delamere shall wave their long arms in despair, and groan over the slaughtered sons of Albion. Then shall the Eagle drink the blood of Princes from the headless cross. But, no more. These words, and more also, shall be spoken by a Cestrian—be recorded and be believed. Now, haste thee home, for it is not in thy time, these things shall be !”

He obeyed and left the cavern; he heard the Iron Gates close—he heard the bolts descend—he turned to see them once again, but they were no longer visible! He marked the situation of the place, and with a quick step, he pursued his way to Mobberley. He related his adventure to his neighbours, and about twenty of them agreed to accompany him in search of the Iron Gates. They went—- they searched—but in vain! No trace remained; and though centuries have rolled away since that night, no person has ever beheld the Iron Gates.